NLRB: Graduate Students at Private Universities May Unionize

From Inside Higher Education

From Inside Higher Education

In a blow to private institutions and a boon to their graduate student employees, the National Labor Relations Board ruled Tuesday that graduate research and teaching assistants are entitled to collective bargaining under the National Labor Relations Act.

Graduate student unions at public institutions are common, as students’ collective bargaining status on public campuses is governed by state law. But the NLRB oversees graduate student unions on private campuses. Tuesday’s decision in favor of a graduate student union bid at Columbia University effectively reverses an earlier NLRB ruling against a graduate student union at Brown University, which had been the law of the land since 2004. The decision also overturns a much longer-standing precedent against collective bargaining for externally funded research assistants in the sciences.

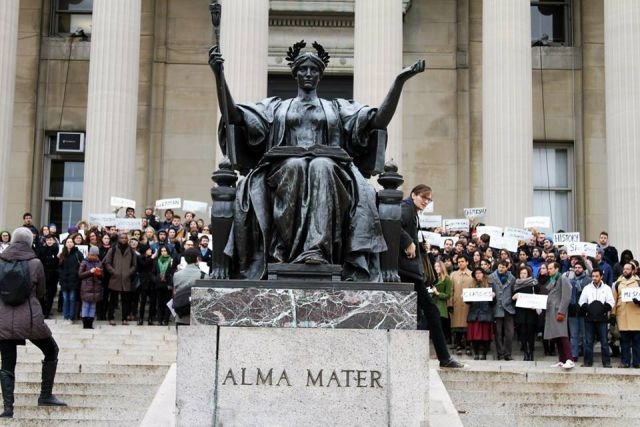

Graduate students at Columbia and elsewhere celebrated Tuesday’s decision, saying they planned to move forward with their union drives. While many professors applauded the decision to recognize students as legitimate workers, other groups described it as reckless, with the potential to transform — for the worse — the relationship between institution and student. Columbia or other universities could move to challenge the ruling in federal court.

Columbia’s graduate assistants are affiliated with the United Auto Workers, but there are active drives on a number of other campuses affiliated with different unions, including the American Federation of Teachers and Service Employees International Union. The latter was a key player in a wave of recent adjunct faculty union drives.

Graduate student union momentum at Cornell, Duke, Harvard, Northwestern, Saint Louis and Yale Universities and the University of Chicago, among others, had only increased in anticipation of Tuesday’s decision. Graduate students gathered at Duke to celebrate the NLRB ruling and to demand a union (at right). Research and teaching assistants at the University of Rochester and Syracuse University also announced organizing drives following Tuesday’s decision.

“We are excited we have finally reached this important milestone and look forward to a speedy, fair election so we can demonstrate our majority support and get into bargaining as soon as possible,” Olga Brudastova, a Ph.D. candidate in civil engineering and mechanics at Columbia, said in a statement.

Aaron Greenberg, a Ph.D. candidate in political science at Yale and chair of its would-be graduate employee union, affiliated with Unite Here, called the decision “really exciting,” and said it’s “making history for graduate students at private colleges across the country, in that the law is recognizing the work we do and that we have the right to unionize.”

Columbia’s graduate student union held a union vote in 2002, but ballots were destroyed following the 2004 NLRB decision concerning Brown. On Tuesday, student workers sent a letter to the university’s central administration asking it to honor the new decision and allow a fair and free election.

Columbia, along with its Ivy League peers, has opposed graduate students’ right to unionize, including in a joint amicus brief filed with the NLRB as part of the United Auto Workers case.

The university said in a statement Tuesday that it’s reviewing the ruling, but that it “disagrees with this outcome because we believe the academic relationship students have with faculty members and departments as part of their studies is not the same as between employer and employee.”

First and foremost, Columbia said, “students serving as research or teaching assistants come to Columbia to gain knowledge and expertise, and we believe there are legitimate concerns about the impact of involving a nonacademic third party in this scholarly training.”

Whatever the outcome, it added, “we will continue our ongoing efforts to make Columbia a place where all students can achieve the highest levels of both intellectual accomplishment and personal fulfillment.”

Peter Salovey, president of Yale, said in a separate statement that the “mentorship and training that Yale professors provide to graduate students is essential to educating the next generation of leading scholars” and that he’d “long been concerned that this relationship would become less productive and rewarding under a formal collective bargaining regime, in which professors would be ‘supervisors’ of their graduate student ‘employees.’”

Although “I disagree with the NLRB’s decision announced today,” Salovey continued, “it presents an opportunity for our campus to engage in a robust discussion about the pros and cons of graduate student unionization. We should embrace the chance to debate this important issue, and we will conduct this campus discussion in a manner that is proper for a university — free from intimidation, restriction and pressure by anyone to silence any viewpoint.”

While the NLRB has historically flip-flopped on whether graduate student assistants are employees or students, Tuesday’s 3 to 1 decision asserts that they can be both.

“The board has the statutory authority to treat student assistants as statutory employees, where they perform work, at the direction of the university, for which they are compensated. Statutory coverage is permitted by virtue of an employment relationship; it is not foreclosed by the existence of some other, additional relationship that the [National Labor Relations] Act does not reach,” says the decision.

As to Columbia’s argument that being legally recognized employees could interfere with students’ education and training, the decision asserts that’s simply not the case. The idea “is unsupported by legal authority, by empirical evidence or by the board’s actual experience,” the decision says. It cites a 2013 study suggesting that unionization did not have a negative effect on student outcomes at public institutions, for example. Unionized graduate students reported higher levels of professional support, better pay and similar academic freedoms, according to the study.

Past bans on the unionization of graduate students at private universities “deprived an entire category of workers of the protections of the act without a convincing justification,” the NLRB decision says. It not only reverses the Brown ruling concerning graduate teaching and some research assistants, but also a board decision dating back to the 1970s asserting that externally funded research assistants in the sciences are ineligible for collective bargaining. The case, known as Leland Stanford, concerning physicists at Stanford University, excluded externally funded research assistants from union membership on the grounds that they were largely pursuing their own research agendas, as required to obtain their Ph.D.s — not performing any specific service for the university.

“The premise of Columbia’s argument concerning the status of its research assistants is that because their work simultaneously serves both their own educational interests along with the interests of the university, they are not employees under Leland Stanford,” the new decision says. “To the extent Columbia’s characterization of Leland Stanford is correct, we have now overruled that decision. We have rejected an inquiry into whether an employment relationship is secondary to or coextensive with an educational relationship. For this reason, the fact that a research assistant’s work might advance his own educational interests as well as the university’s interests is not a barrier to finding statutory-employee status.”

Nothing in the board’s decision precludes even undergraduate students who perform some kind of service for the university in exchange for compensation from seeking collective bargaining. Of course, most research positions and assistantships are held by graduate students.

The three board members who backed the decision were Mark Gaston Pearce, chair, Kent Y. Hirozawa and Lauren McFerran.

Philip A. Miscimarra voted against the decision and issued a dissent.

“My colleagues disregard” the enormous expense faced by many students these days to finance higher education, he wrote. “Congress never intended that the [labor relations act] and collective bargaining would be the means by which students and their families might attempt to exercise control over such an extraordinary expense.” Miscimarra warned of the “havoc” that could be wreaked as the board, in his view, changed the fundamental nature of studentship at a university. For example, he said, graduate students could engage in teaching strikes.

The American Association of University Professors, which argued in an amicus brief in the Columbia case that collective bargaining could improve graduate students’ academic freedom, applauded the majority decision Tuesday.

“This is a tremendous victory for student workers, and the AAUP stands ready to work with graduate employees to defend their rights, including rights to academic freedom and shared governance participation,” Howard Bunsis, chair of the association’s Collective Bargaining Congress and a professor of accounting at Eastern Michigan University, said in a statement. “Graduate employees deserve a seat at the table and a voice in higher education.”

Randi Weingarten, president of the AFT, said that graduate student employees at private institutions, “just like their peers in public universities across the country, deserve the right to organize to have a real say over their wages and conditions.” The NLRB “took a hard look at the flawed reasoning in Brown and concluded, rightly, that grads should be afforded exactly the same workplace rights as their colleagues.”

The National Association of Graduate and Professional Students argued in its own amicus brief that graduate students need to be recognized for the work and service they provide their institutions. At some members’ universities, the brief said, graduate students shoulder 30 percent of the teaching load.

“Today is a good day,” said Kristofferson Culmer, president and CEO of the association. “It has been long established that employees in this country have a right to have a voice in their workplace, and today that right has finally been extended to all graduate-professional student employees.”

But others sided with Miscimarra, criticizing the decision.

Senator Lamar Alexander, a Tennessee Republican and chair of the Senate Committee on Health, Education, Labor and Pensions, said the NLRB is “completely confusing the entire reason students enroll in the first place; if I’m earning [a university degree] my primary purpose and benefit during my time there is to gain the skills I need to launch myself into the career and the future I want — not to garner wages as an employee of the university.” He called the decision “a shameless ploy to increase union membership rather than a genuine attempt to help students.”

Peter McDonough, vice president and general counsel of the American Council on Education, said his organization was “greatly disappointed” that the NLRB “overturned decades of legal precedent and academic practice with a ruling that represents a sweeping expansion of federal authority.”

The “misguided decision turns all students into potential employees who could be organized, even undergraduate students in federal work-study positions,” McDonough said. “Such a development would decrease opportunities for campus jobs that help students, particularly those from low- and middle-income families, finance their education and drive up administrative costs. … In an era where so many are worried about the costs of college, this is a big step in the wrong direction.”

Joseph Ambash, managing partner with Fisher Phillips in Boston, successfully argued the Brown case before the board back in 2004. He said in an interview Tuesday that NLRB decision was reckless in scope.

“The NLRB basically identified any student — whether an undergraduate or master’s or Ph.D. candidate — at any private-sector institution as an employee so long as that student provides some institutional service for which they receive some form of compensation,” Ambash said. “The sweep of this decision is so broad that it’s really likely to transform many, many academic institutions into, quote, workplaces.” Regarding the research assistant determination, he added, “this is the first time universities are going to have to collectively bargain about curriculum requirements.”

Other critics pointed out what they saw as a discrepancy — or a hypocrisy — between the board’s 2015 decision not to assert jurisdiction over Northwestern’s football team in its bid to form a union and today’s ruling. But William Herbert, executive director of the National Center for the Study of Collective Bargaining in Higher Education and the Professions at Hunter College of the City University of New York, said the cases defy comparison — and that the board actually observed in a footnote in the Northwestern decision that its lack of jurisdiction there did not bear on the question of the graduate student workers.

Herbert said he thought Tuesday’s ruling read as a “back to basics” approach by the board about what Congress’s intent was behind the original labor relations act. Herbert said it would be some time before any official challenge to the ruling could arise in court, since process dictates that a union election would first have to be held.

Ambash said some kind of challenge is “highly anticipated,” and that — in his view — “the courts would likely have a different opinion on the appropriateness of collective bargaining among students.”

An NLRB ruling affirming the right of graduate students at private universities has been a major goal of academic labor during the Obama administration. Prolonged fights over NLRB nominees, however, slowed down the process by which the board could rule. Many have expected a ruling in favor of the UAW. In July, Columbia awarded an unprecedented pay increase to its graduate workers ahead of the likely ruling. Cornell promised its graduate employees a fair and expeditious election in the event of an NLRB decision in favor of these unions.

Here is a timeline on the NLRB and graduate student unionization:

2000: NLRB — in case involving NYU and UAW — rules that graduate teaching assistants are eligible for collective bargaining and can be considered employees.

2002: NYU recognizes the UAW union for its graduate students, becoming the first private university to do so.

2004: NLRB — in case involving Brown University and the UAW — reverses the 2000 ruling and says graduate students cannot be considered employees entitled to collective bargaining.

2005: NYU withdraws recognition of the UAW.

2005-6: Graduate teaching assistants go on strike at NYU, seeking to force the university to restore recognition, but strike fizzles out without such recognition.

2011: Regional NLRB official, in response to new petition from NYU graduate students to unionize with UAW, rules that the 2004 decision that grad students lack collective bargaining rights is still in place, but questions logic of that ruling, which is then appealed to full NLRB.

2012: NLRB announces it will use the appeal on behalf of NYU grad students to reconsider the 2004 ruling.

2013: NYU and UAW announce compromise under which the appeal to NLRB will be withdrawn.

2015: NLRB agrees to reconsider whether graduate students have collective bargaining rights.

2016: NLRB rules that graduate students have the right to collective bargaining.